Up until last week, discrete graphics, the high-end parts you would use if you were into gaming, CAD/CAM, AI development, metaverse creation, picture and movie editing, architecture, animation, or any other field (like engineering) that required high-performance graphics, you had a choice of two vendors: AMD which was the leader in value and more bang for the buck, and Nvidia which tended to lead in absolute performance.

While those two firms often trade places, the battlefield was well defined between them, but both under-penetrated the laptop sector because the focus on laptops, at least up until the pandemic, was efficiency and battery life.

Intel was dominant in laptops, but not with discrete graphics. Thus, it had much lower-performing integrated graphics. You could get more expensive mobile workstations, gaming laptops with GPU options, or some business notebooks that had GPU upgrades, but many laptops used base-level Intel graphics.

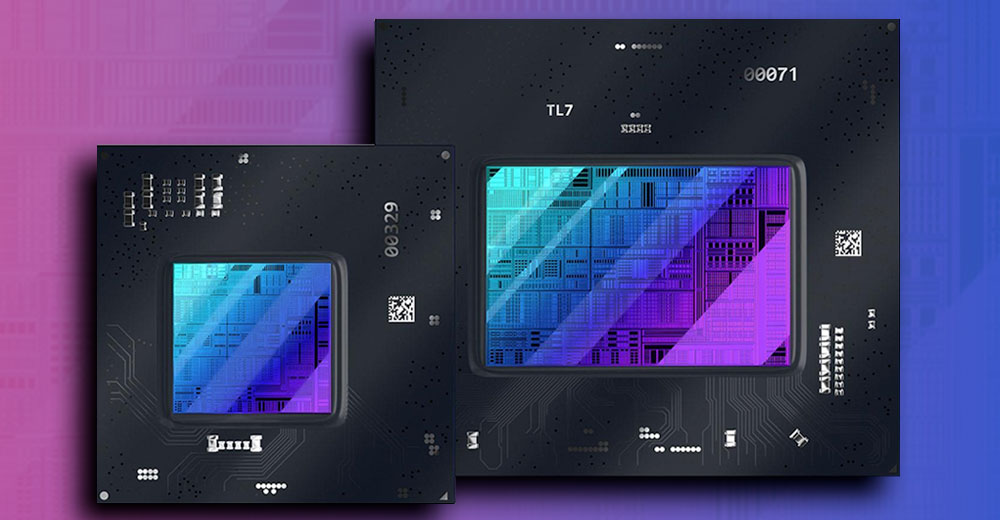

Therefore, Intel targeted laptops with its initial Arc offering because that path is far easier in a market the company already dominates, as opposed to competing with GPU cards in the desktop market — or even mobile workstations which require software certifications — or gaming rigs which require the game companies to directly support the hardware for higher performance.

Let’s talk about Intel Arc A-Series graphics, and then close with my product of the week, a 34-inch conferencing monitor from HP.

The Importance of Discrete Graphics

If you are a gamer or use your laptop to work on graphics- or AI-intensive projects, you live on discrete graphics because integrated graphics just aren’t good enough. Typically, that pushes you into a much more expensive line of laptops, like focused gaming or workstation rigs which are quite pricey.

The graphics are critical to your work product and, if you game, a GPU can improve your time on target, your ability to see stealthier players or NPCs, and potentially give you a significant competitive advantage.

More recently, discrete graphics cards have begun to convert older games to high resolutions, making them look more like current games and far more fun to play as a result. They can upgrade some video content in much the same way, broadening the interest in discrete GPUs.

Users often had a choice. They could get this wonderful performance on a desktop computer but not be very mobile, or they could give it up to be mobile and have a long battery life. But, as time progresses, both AMD and Nvidia have improved their performance envelope for their GPUs.

Still, with laptops, Intel’s integrated graphics, due to both cost and battery life benefits, is often preferred. A lot of us, therefore, have a desktop computer we game off, and a laptop for when we need to work on the road.

This provides an interesting market entry point for Intel which can leverage its integrated graphics and CPU supremacy on laptops to gain GPU dominance on the same platform with far less headroom than it could in the desktop space.

Then, once successful on laptops, Intel can use that beachhead to go after the desktop GPU market owned by AMD and Nvidia if, and this now becomes a given, it gets the needed game developer support and software certifications.

Getting Support

One of the big issues with entering the discrete graphics market is that you need that software support from game and professional applications that use discrete GPUs. But typically, you will not get that support until there is a critical mass of the hardware in market; and you will not get to critical mass if the users do not see you have game developer and software support.

There is one caveat, however: if the developers believe you will get to critical mass, they will move early. Intel, due to its mobile dominance, has a credible argument that getting to critical mass with mobile, not desktop, is a given and thus should be able to drive some, if not all, major developers to its platform before its installed base gets to that critical mass.

This is not a sure thing, but Intel claims to be getting substantial support, and it is this dynamic of having a huge footprint in the existing mobile market that provides this unique opportunity.

What I Am Looking for Most

Intel presents a compelling message on peer performance, but what I’m waiting to see is whether it will do the game upgrade thing better than its new peers, AMD and Nvidia. My current game of choice is a re-release of an older game I was hooked on almost two decades ago that really needs a graphics uplift. If Intel can, as it claims, upgrade that game, I will be sold.

Given Intel’s approach to upsampling on paper is a blend of the best parts of AMD’s and Nvidia’s approach, there is a decent chance it will be able to do better what AMD and Nvidia do now. Of course, the downside is I rarely game on a laptop, but I do when I travel — which I am starting to do again.

Fingers crossed, that the new Intel Arc mobile graphics knock my socks off.

Wrapping Up

Going after a market dominated by one or two large vendors from behind is a difficult task. The best approach is to first get a beachhead in an area where those companies are not particularly strong and you either are or can be.

In Intel’s case, the beachhead will be laptop computers where Intel remains dominant, and that could initially position it very well against the traditional owners of this segment.

Be aware there is always a risk with first edition offerings and, while Intel’s experience in the PC segment and its relationship with Microsoft is near legendary, success is still not certain and will require a high degree of execution. Fortunately for Intel, it’s now led by Pat Gelsinger, one of the best and most focused executives I have ever met.